About the Books

Mystic Visions: Black Elk's Great Vision Clarified

The Essential Companion to the Classic Black Elk Speaks

by John G. Neihardt

Based on the compelling vision of Nicolas Black Elk as written by: John G. Neihardt in Black Elk Speaks, Quentin H. Young has unlocked its messages, as he clarifies each detail of the vision. A vision given for all people of the world then, now, and for the future, and explains why a vision given to a young Lakota boy in 1872 has relevance today.

Black Elk: Black Elk noticed all the dancing horses turning into animals of every type and into every bird that was and flew back to where all the horses had come from, the west, north, east, and south.

Clarification: This statement takes us a little further in-depth. The dancing horses of every color and without number changing into animals of every type and all the birds, are making a statement, “Mitakúye Oyasin.” The fact they all returned to the four quarters from whence the horses came and vanished, bolsters the idea the grandfathers were showing Black Elk his relationship with all things within the four quarters of the World. The Grandfathers would not establish this type of relationship and then exclude the wasichu (non-Indian). This will become more apparent as we move deeper into this vision.

Taken From Chapter 19 of Mystic Visions

The following is a summary account from John G. Neihardt's: "Black Elk Speaks", the author's postscript, Black Elk sends his last prayer from Harney Peak.

Black Elk stood at the top of Harney Peak, renamed Black Elk Peak in 2016. Holding his pipe in his left hand and dressed in his long red johns. With outstretched arms, he sent his prayer to the six grandfathers. Tears ran as he spoke aloud stating the tree did not blossom. And he has turned away and done little for the people. He said, "I stand at the top of the world where you took me as a young boy and instructed me, for I am just an old man now, and the tree is dead."

He went on to say that this might be the last time he remembers the great vision they gave him. He asked the great mystery, if any part of the root lives, then nurture it, that the tree may bloom with birds singing among the leaves. He asked the great mystery to hear his prayer, not for him, but for the people that they may find the "good red road" once again. He stood with tears running and addressed the six grandfathers saying, "Oh make my people live".

Black Elk

Photo courtesy of John G. Neihardt Trust, Western Historical Manuscript Collection, Columbia

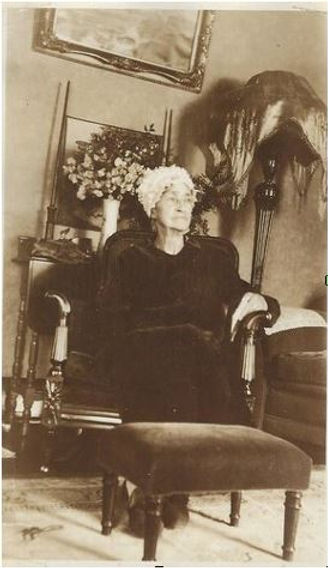

Eliza Jane Milton

Rose Leaf Eliot

Rose Leaf Eliot, 1878-1941. My Sicangu Lakota Grandmother with my Mother Rose Mary, taken some time in July 1918. Rose Leaf married Clarence Likens, and they had one child, my mother Rose Mary Likens.

Eliza Jane Milton, my Great Grandmother, 1849-1929. Eliza was a full-blood Sicangu Lakota borne in Nebraska. In 1855, a soldier took Eliza from the battlefield of the Blue Water Fight and gave her to the Milton’s of Missouri. Soon after, Eliza was adopted by them and raised as a white. She married James Eliot and had seven children, six girls, and one boy. It was said that wherever James and Eliza traveled the whites called him a squaw man (a derogatory statement).

~~ Finding Lara: From the Other Side ~~

My name is Quentin H Young, author of Mystic Visions: Black Elk's Great Vision Clarified. I met Chris Dennison when I was fifteen, and he was eleven. Chris is Lakota (Sioux) from his mother's side of the family and is related through my mother's Lakota side of the family which makes Chris my third cousin.

When I began writing Finding Lara: From the Other Side, it challenged me as an author, it required me to step out of the safe place of spiritual writing and into the dark corners of rape, child abuse, and prejudice thinking: not about racial injustice but about how society treats people who are physically different.

In early 2022, I had the rare privilege of recording an interview with Chris about his early struggles as a winkte. The word wiŋkte (wink-tay) is a Lakota word, for hermaphrodite. The human hermaphrodite is not a true hermaphrodite, being both male and female. The medical field refers to this condition as Intersex. Traditional Lakota see the wiŋkte as being sacred whereas, non-traditional people see them as either gay or lesbian.

The first three chapters in this book took place in Chris’s early years, they contain descriptive content with respect to sexual abuse, and rape. What is important to understand is, through-

out each chapter Chris gained immense understanding with respect to his physical body. This would help him find peace of mind and move beyond the abuse, bringing him closer to discovering who Lara is, and where she comes from.

These writings are both controversial and educational. This book is not intended for young children. With parental guidance and approval, transgender people 15+ could find this book helpful before they begin taking hormones and undergoing gender reassignment surgeries.